How do general economic conditions and economy-wide default risk shocks affect corporate bond returns, especially past winners and losers? In the May 2012 draft of their paper entitled “Sources of Momentum in Bonds”, Hwagyun Kim, Arvind Mahajan and Alex Petkevich investigate the relationship between U.S. corporate bond momentum portfolio returns and U.S. aggregate default risk. They measure the momentum effect as average monthly gross returns of overlapping hedge portfolios formed each month by buying (selling) the equally weighted tenth of bonds with the highest (lowest) total cumulative returns over the past six months and holding for six months, with a skip-month between ranking and holding intervals. They measure aggregate default risk as the prior-month yield spread between the Moody’s CCC corporate bond index and the 10-year U.S. Treasury note. They define default risk shocks as deviations from the linear relationships between default risk this month and its values the prior two months. They define high (low) default risk shock conditions as those above (below) the inception-to-date median value of the series. Using price and yield data for all listed U.S. corporate bonds (excluding convertible bonds, asset-backed securities and bonds with very low capitalization) during January 1995 (101 bonds) through December 2010 (2,513 bonds), they find that:

- Over the entire sample period, the gross momentum effect for U.S. corporate bonds is an insignificant 0.19% per month.

- However, the gross momentum effect is elevated (0.61% per month) during months after high default risk shocks and depressed (-0.26% per month) during months after low default risk shocks. Of 192 monthly observations, 100 (92) follow high (low) default risk shocks.

- Results are reasonably consistent for 1995-2002 and 2003-2010 subperiods, with gross momentum effects of 0.42% per month and 0.84% per month, respectively, during months after high default risk shocks.

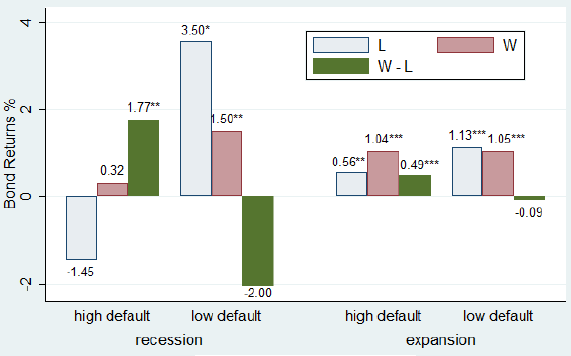

- Over the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER)-designated U.S. economic cycle (see the chart below):

- The strongest gross momentum effect occurs during months after high default risk shocks when the economy is contracting (1.77% per month). [However, the effect derives largely from poor performance of losers, rendering a momentum strategy impractical for most investors.]

- The gross momentum effect is also evident during months after high default risk shocks when the economy is expanding (0.49% per month), but the effect disappears during months after low default risk shocks for expansions.

- Excluding low-rated bonds eliminates the momentum effect, even during months after high default risk shocks.

- U.S. government bonds display no momentum effect, but it appears weakly during months after high U.S. default risk shocks for bonds of other countries traded in the U.S. market.

The following chart, taken from the paper, summarizes the momentum effect for U.S. corporate bond portfolios during months after high and low default risk shocks, segmented by NBER contraction (recession) and expansion conditions during 1995 through 2010. The winner minus loser (W-L) returns measure the momentum effect. Superscripts *, ** and *** indicate progressively stronger statistical significance (which depends on return magnitudes, return variabilities and subsample sizes).

Results indicate that the bond momentum effect (W-L) is significant under both weak and strong economic conditions, but only during months after high default risk shocks.

Since shorting specific corporate bonds is problematic, the import for long-only bond investors is to avoid (focus on) corporate bonds during recessions after prior-month high (low) default risk shocks.

In summary, evidence indicates that bond investors should avoid (exploit) U.S. corporate bonds during recessions after prior-month high (low) shocks to aggregate U.S. default risk.

Cautions regarding findings include:

- As noted, most investors cannot short specific corporate bonds, undermining the practical import of the main themes of the study.

- Return calculations are gross, not net. Including reasonable trading frictions, which tend to be high for momentum strategies because of high turnover, would reduce reported returns and may affect findings. It is plausible that speculative grade bonds and months after large increases in aggregate default risk relate to relatively high trading frictions.

- The sample period is not long in terms of secular inflation trends.

- Statistical significance tests assume tame return distributions.