Do investors systematically and exploitably underreact to deviations in firm fundamentals from recent averages? In their January 2020 paper entitled “Anchoring on Past Fundamentals”, Doron Avramov, Guy Kaplanski and Avanidhar Subrahmanyam investigate how deviations of quarterly firm accounting variables from averages over recent quarters relate to future returns across stocks. They first construct a stock performance deviation index (PDI) based on seven variables: (1) cash and short-term investments, (2) retained earnings, (3) operating income, (4) sales, (5) capital expenditures, (6) invested capital and (7) inventories. They then each month for each stock starting June 1977:

- Calculate the deviation for each variable as the difference between its most recent quarterly value and its average over the preceding three quarters, scaled by total assets.

- Rank each deviation (in percentiles) relative to deviations for the same variable for all stocks.

- Calculate PDI for a stock as the equally weighted average of percentile rankings across all seven variables.

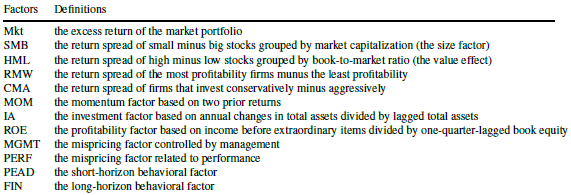

They extend this approach to a more comprehensive fundamental-based deviation index (FDI) that considers deviations of all Compustat accounting variables plus 14 commonly used accounting ratios, with weights of deviation percentile rankings optimized via least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression starting January 1979. For all variables, if the exact release date is unavailable, they assume a 60-day delay in release. For portfolio tests, they calculate returns to hedge portfolios that are long (short) stocks in the top (bottom) tenth, or decile, of PDIs or FDIs, with holding intervals ranging from one to 24 months. Using monthly data needed to construct PDI, FDI and 30 style, technical, fundamental and liquidity control variables across a broad sample of reasonably liquid U.S. common stocks with positive book values and prices over $5 during January 1976 through October 2017, they find that: Keep Reading