Is buying assets during banking crises, when assets appear to be at deep discounts, an attractive long-run strategy? In their January 2021 paper entitled “Investing in Crises”, Matthew Baron, Luc Laeven, Julien Penasse and Yevhenii Usenko investigate asset returns across several years before and after banking crises, for which they identify the onset (first month) in three ways:

- Systemwide banking panics (as specified in a prior paper).

- Multiple major government interventions (as specified in a prior paper).

- 30% drop in a country’s bank stock index (bank equity crash).

They test trading strategies in which a U.S. investor exploits banking crises around the world as they occur and otherwise holds U.S. Treasury bills (T-bill). They focus on bank stock and other (non-financial) stock indexes, but also consider government bonds, currencies and residential real estate. Using monthly asset index returns in both local currencies and U.S. dollars, monthly U.S. T-bill yield, crisis starting months and economic data across 44 developed and emerging market countries during 1960 through 2018, they find that:

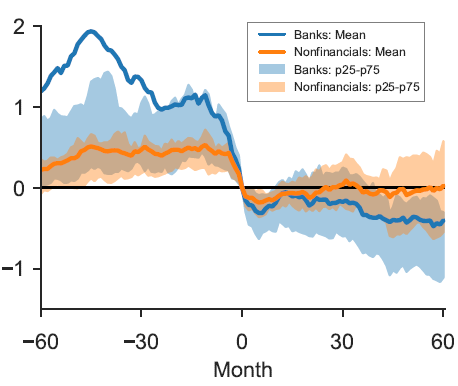

- Returns of equity (see the chart below) and other asset classes are generally unattractive after banking crises, whether measured in local currencies or U.S. dollars, in excess returns or real returns.

- There is high risk for buying during crises (especially bank stocks), as indicated by a large variance of outcomes across crises and by the frequency of double-dips.

- Crisis buying/T-bill switching strategies, whether for stocks or other asset classes, fail to beat an international buy-and-hold strategy on either an absolute or a risk-adjusted basis. For bank stocks, they consistently generate negative alphas.

- Exceptionally good timing (buying when prices bottom on average six months after the acute phase) beats buy-and-hold by at most a few percent for non-financial stocks and still underperforms for bank stocks.

- Over the long run, banking crises are cash flow shocks rather than discount rate shocks, with a sudden collapse in prices (and temporarily high price-to-dividend ratios) followed by future deterioration in dividends.

- The extent of debt defaults and debt overhang at the time of the crisis best explains variation in investment outcomes. Fiscal/monetary policy actions at the time of the crisis and macroeconomic indicators have little correlation with stock market outcomes. Investors appear not to appreciate the long-lasting economic consequences of debt overhang, leading them to overestimate the speed of recovery.

- Results on bank stock underperformance suggest that government bank bail-outs often lead to substantial taxpayer losses. The sharp rebound of the U.S. stock market after 2008 is an exception.

The following chart, taken from the paper, tracks average cumulative excess returns in U.S. dollars (relative to the U.S. T-bill yield) of bank and non-financial stock indexes from five years before to five years after 50 systemwide banking panics over the full sample period. Also shown are 25th to 75th percentile ranges of panic returns. Notable points are:

- Before crises, returns are strong, suggesting that the best trading strategies may involve riding the bubble during credit booms.

- Starting after onset (month 0), average returns for (especially) bank stock indexes and non-financial stock indexes are weak. Both indexes initially trend down to a trough in six month and do not recover after five years.

- 25th-75th percentile ranges generally fall below respective averages, suggesting mostly poor performance with averages pulled up by a few positive outliers.

Results are similar for local currencies and real returns. Results are also qualitatively similar for crises defined by multiple major government interventions and by bank equity crashes.

In summary, evidence suggests the conventional wisdom that investors should buy during crises when others are fearful (or financially constrained) is flawed.

Cautions regarding findings include:

- Sample sizes are not large, and comparability of events is arguable.

- The authors do not support their speculation that riding the bubble during credit booms may be more attractive than buying dips after crashes.

- The authors do not consider strategies that seek to avoid parts of market crashes that generally accompany financial crises.