Do returns for “smart beta” indexes, constructed to exploit research on one or more factors that predict individual stock returns, reliably predict returns for exchange-traded funds (ETF) introduced to track them? In the June 2020 version of their preliminary paper entitled “The Smart Beta Mirage”, Shiyang Huang, Yang Song and Hong Xiang compare returns of smart beta indexes before and after listings of corresponding smart beta ETFs (see the illustration below). They then explore four potential explanations of differences: (1) offeror timing of ETF introduction based on underlying factor performance, (2) offeror timing of ETF introduction based on underlying index performance, (3) long-term trends in factor premiums and (4) data snooping bias. Using introduction dates for 238 U.S. single-factor and multi-factor equity smart beta ETFs listed between 2000 to 2018 and price data for matched smart beta indexes as available through December 2019, they find that:

- For more than half of smart beta indexes, index construction precedes corresponding ETF listing by less than six months. In other words, there is usually very little live testing of indexes before introduction of tracking ETFs.

- The average smart beta index generates an average 2.77% (-0.44%) per year relative to the overall stock market before (after) corresponding ETF listing.

- Controlling for factor-themed benchmark returns indicates that neither timing of ETF introductions nor long-term factor performance trends explain post-ETF deterioration.

- Evidence of data snooping in smart beta index design is strong, with indexes most susceptible to snooping exhibiting greatest post-ETF declines. Specifically, post-ETF deterioration is significantly worse:

- Among indexes constructed within six months of ETF introduction (little or no live verification of backtesting) and containing the ETF offeror’s name (captive backtesting) than for other indexes.

- Among small ETF offerors (plausibly more motivated to attract investors via snooping) than large offerors.

- Among multi-factor (with complexity supportive of snooping) than single-factor indexes.

- Data snooping apparently attracts investors. A one standard deviation increase in pre-ETF, market-adjusted index return indicates a 6% increase in monthly investment flow during the year after ETF listing.

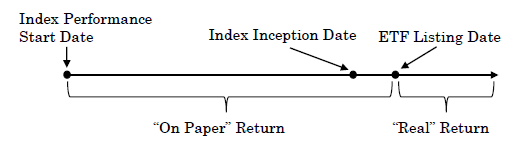

The following illustration, taken from the paper, summarizes the typical timeline for a smart beta index, highlighting the break point between pre-ETF (“On Paper”) return and post-ETF (“Real”) subperiods. Live index testing occurs between index inception date and ETF listing date.

In summary, evidence indicates that investors should be skeptical of smart beta index returns from before launch of the corresponding ETF.

Cautions regarding findings include:

- As noted by the authors, findings are “preliminary and incomplete” and may be revised.

- Sample periods for many index-ETF observations are short.