Are government bond returns exploitably predictable? In their June 2020 paper entitled “Predicting Bond Returns: 70 Years of International Evidence”, Guido Baltussen, Martin Martens and Olaf Penninga examine predictability of international 10-year government bond returns with emphasis on two subsamples, January 1950 through September 1981 (mostly rising interest rates) and October 1981 through May 2019 (mostly falling rates). They consider five predictive variables, each transformed into a binary signal:

- Yield spread – 10-year government bond yield minus the cash rate, standardized relative to historical values.

- Bond trend – sign of past 12-month 10-year government bond return.

- Past equity return – past 12-month equity index return in excess of cash return, standardized relative to historical values.

- Past commodities return – past 12-month commodity index excess return, standardized relative to historical values.

- Combination – equal-weighted combination of signals 1 through 4.

They use a spliced 10-year government bond sample, using excess return on a representative bond index before inception of associated futures and futures returns thereafter. Using monthly returns for 10-year government bond indexes/futures and cash rates for Australia, Canada, Germany, Japan, UK and U.S. during January 1950 (except October 1961 for Japan) through May 2019 (7,497 monthly returns), they find that:

- Average annualized gross 10-year government bond excess returns globally (equal-weighted across countries) are 2.0% for the full sample period, -0.3% for the early subperiod and 3.9% for the recent subperiod, with annualized gross Sharpe ratios 0.44, -0.07 and 0.78, respectively.

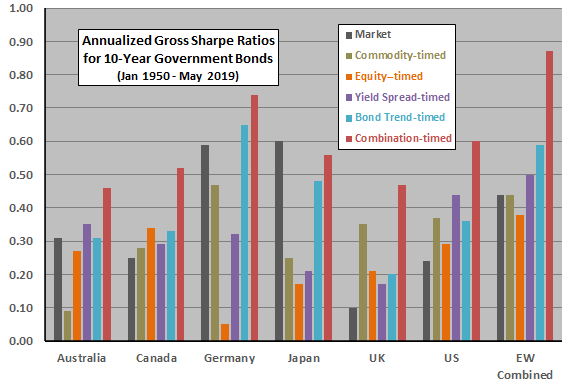

- Strategies based on individual bond return predictors are not consistently attractive compared to continuous long-only positions (see the chart below).

- However, average pairwise correlation between individual predictor strategy returns across countries is just 0.48, so that annualized gross Sharpe ratio for the combination strategy is attractive in each country and an impressive 0.87 globally over the full sample period (again, see the chart below).

- Moreover, the combination strategy:

- Performs well across major subperiods, with annualized gross Sharpe ratio 1.09 (0.73) in the early (late) subperiod.

- Is reasonably consistent across decades, with annualized gross Sharpe ratio ranging from 0.33 during 2000-2009 to 1.15 during 1970-1979 (and 0.58 in the last decade).

- Exhibits predictive power in both good and bad bond markets (but not much in middling bond markets).

- Is robust across economic recessions and expansions, times of high and low inflation, and equity bull and bear markets.

- Return predictability holds in a further test across nine additional developed country government bond markets over the same sample period.

- Bond market predictability relates to predictability of inflation and economic growth.

- Global stocks-global bonds mean-variance allocation tests indicate that substituting the combination government bonds timing strategy in place of continuous long bond positions nearly doubles portfolio annualized gross Sharpe ratio (from 0.34 to 0.66).

- Assuming one-way trading frictions of 0.06%, accounting for combination strategy bond portfolio costs reduces Sharpe ratios by only 0.04-0.05, depending on assumptions.

The following chart, constructed from data in the paper, summarizes annualized gross Sharpe ratios for major 10-year government bond markets without and with various timing strategies as described above. Results for strategies based on individual signals are mixed, but the combination strategy is consistently attractive.

In summary, evidence indicates that government bond return predictability offers exploitable opportunities to investors.

Cautions regarding findings include:

- Some investors may not be able to achieve the assumed 0.06% level of trading frictions. Further, applying this futures-based level of frictions to the part of the sample preceding availability of futures is optimistic.

- The methodology described (especially for signal combination) is beyond the reach of most investors, who would bear fees for delegating to a fund manager.