What are the essential points from the stream of research on low-volatility investing? In their August 2019 paper entitled “The Volatility Effect Revisited”, David Blitz, Pim van Vliet and Guido Baltussen provide an overview of the low-volatility (or as they prefer, low-risk) effect, the empirical finding in stock markets worldwide and within other asset classes that higher risk is not rewarded with higher return. Specifically, they review:

- Empirical evidence for the effect.

- Whether other factors, such as value, explain the effect.

- Key considerations in exploiting the effect.

- Whether the effect is fading due to market adaptation.

Based on findings and interpretations on low-risk investing published since the 1970s, they conclude that:

- Low-risk investing is now widely accepted and variously called low-volatility, managed volatility, minimum volatility, minimum variance, defensive or conservative.

- The low-risk effect is robust:

- Within all major developed and emerging stock markets.

- Within stocks of different market capitalizations.

- Within and across industries.

- Within every asset class.

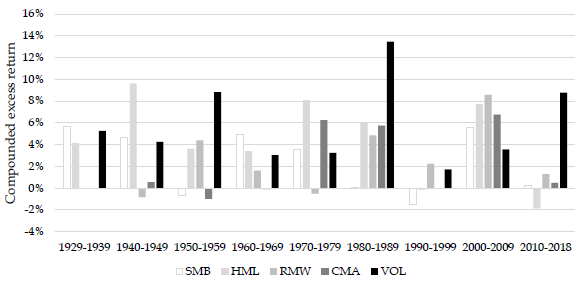

- Over time. Among size, value, profitability, investment and volatility long-short equity factors, volatility is the only one with a positive gross premium in every decade since the 1930s (see the chart below).

- During 1940 through 2018, the average gross annualized volatility factor premium is 5.8% with volatility 9.0%, translating to gross annualized Sharpe ratio 0.65. Among size, value, profitability, investment and volatility factors, volatility is statistically the most reliable over this sample period.

- However, the low-risk effect does not hold across asset classes. In the long run, stocks beat bonds, and corporate bonds beat government bonds.

- Volatility appears to be the main driver of the low-risk effect, and factors such as value, profitability and interest rate changes do not explain the effect.

- In practice:

- Long-only is the prevalent way to exploit the low-risk effect.

- Turnovers of low-risk portfolios are modest compared to those for other factors.

- The low-risk effect is amenable to combination with other factors, such as value and momentum.

- There is little evidence that the market is adapting to the low-risk effect. Hedge funds and mutual funds typically tilt toward high-risk stocks, and exchange-traded funds (ETF) are in aggregate neutral. Current regulations do not encourage institutional investors to exploit the low-risk effect.

The following chart, taken from the paper, summarizes annualized gross premiums of conventional size (SMB), value (HML), profitability (RMW), investment (CMA) and volatility (VOL) long-short factors by decade since 1929. The volatility factor is the only one with a positive gross premium in every decade. The gross premium is also positive in every 120-month moving window. It is also the only factor with an attractive gross premium during the most recent decade.

In summary, the body of research indicates that low-volatility strategies within asset classes are robust and exploitable.

Cautions regarding conclusions include:

- Implementation and maintenance of low-volatility portfolios are beyond the reach of most investors, who would bear fees for delegating this work to a fund manager.

- Compound abnormal returns tabulated in “Are Low Volatility Stock ETFs Working?” are generally much smaller than those indicated in the chart above.

See also: