Does widespread investor acceptance of the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) of stock returns drive undervaluation of stocks with low past alphas? In his February 2019 paper entitled “The Unintended Impact of Academic Research on Asset Returns: The CAPM Alpha”, Alex Horenstein examines whether such acceptance distorts the U.S. stock market. Specifically, he each year at the beginning of January reforms a betting against alpha (BAA) hedge portfolio that is long (short) stocks with alphas lower (higher) than the median based on monthly returns over the past five years. He then weights stocks according to their respective alpha ranks, rescales the long and short sides separately to have market beta 1.0 and holds for one year. He analyzes performance of this portfolio and eight widely accepted equity factors (size, value, momentum, profitability, investment, short-term reversal, long-term reversion and betting against beta) during three subperiods: (1) pre-CAPM era (1932-1964); (2) CAPM era (1965-1992); and, (3) smart beta era (1993-2015). Using total returns for a broad sample of U.S. common stocks and returns for eight accepted equity factors during January 1927 through December 2015, he finds that:

- The BAA hedge portfolio delivers -0.04% gross monthly CAPM alpha during the pre-CAPM era, 0.54% during the CAPM era and 0.88% during the smart beta era. Regarding CAPM alphas of other factors:

- During the pre-CAPM era, size, value and long-term reversion factors perform poorly. Momentum, short-term reversal (especially) and betting against beta perform well.

- During the CAPM era, momentum, short-term reversal and betting against beta continue to perform well. Value also performs well, with size and long-term reversion relatively weak.

- During the smart beta era, momentum and betting against beta (especially) continue to perform well, but all other factors are relatively weak.

- This BAA performance evolution is present but weaker for a sample restricted to NYSE stocks.

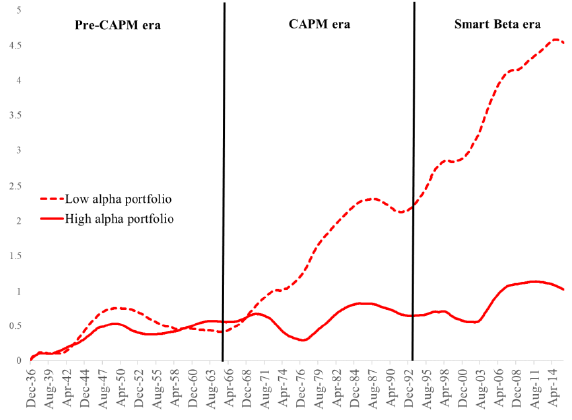

- The growing CAPM alpha of BAA comes predominantly from the low alpha side, which contains stocks neglected by fund managers (see the chart below).

- Low-alpha and high-alpha sides of the BAA portfolio have volatilities similarly greater than average and are therefore sensitive to market liquidity shocks. Sensitivity of the low-alpha side is twice that of the high-alpha side.

- The publication rate of new CAPM-related academic work parallels acceleration of BAA performance, increasing steadily during the CAPM era and much faster during the smart beta era.

The following chart, taken from the paper, tracks cumulative excess returns (relative to the risk-free rate) of the short and long sides of BAA separately for the full sample of stocks across the three eras. Results show that BAA return comes mostly from the long (low-alpha) side, becoming substantial only after the introduction of CAPM in the mid-1960s.

In summary, evidence suggests that academic research on CAPM has created an attractive betting against alpha anomaly and perturbed anomalies correlated with the overall market.

Cautions regarding findings include:

- Findings are gross, not net. Accounting for annual BAA portfolio reformation and costs of continuously shorting high-alpha stocks would reduce performance. Shorting of some stocks as specified may be costly/impractical due to lack of shares to borrow.

- Similarly, returns for other factors are gross and involve varying levels of portfolio reformation frictions and shorting costs.

- In particular, BAA and betting against beta portfolio formation process is unconventional and complicated. See “Back Doors in Betting Against Beta?” for a critique of the approach, arguing that it creates portfolios with close to equal weighting (especially difficult/costly-to-implement).

- Allowing one day for collection/processing of final data for BAA portfolio reformation is optimistic for much of the sample period.

See also the closely related “Just Bet Against Everything?”.