Is a passive investor one who holds all securities in their respective market capitalization weights, or one who never trades? In his October 2016 paper entitled “Sharpening the Arithmetic of Active Management”, Lasse Pedersen challenges the proposition that active trading is a zero sum game that produces an average gross return equal to that realized by passive investors. He argues that holding the market capitalization-weighted portfolio over the long term requires trading as securities enter and exit the market, new shares are issued, old shares are repurchased and authorities reconstitute market indexes. In other words, the market portfolio changes over time such that even passive investors must trade, and they may trade unfavorably with active managers. Also, real passive investors trade for non-investment reasons, again perhaps unfavorably with active managers. Based on the arithmetic of realistic portfolio maintenance, he concludes that:

- An investor who never trades (never participates in initial public offerings or seasoned equity offerings) gradually drifts substantially from the market portfolio. In the case of the U.S. stock market, a static portfolio covers only about 60% of the market after 10 years.

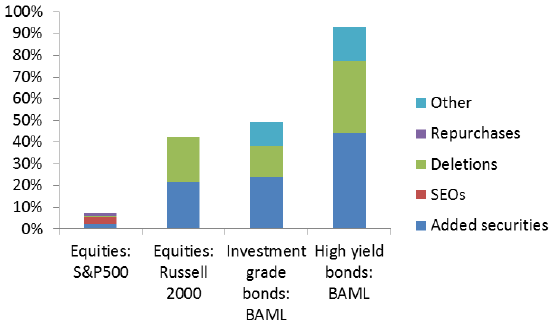

- Active investors can front-run, and thereby capture a premium from, passive investors for securities entering/exiting/changing weights in market (benchmark) indexes. The higher the turnover of a benchmark index, the more opportunities for active investors to capture such premiums (see the chart below).

- An active investor can participate in private equity, venture capital, real estate, raw materials and other private assets, but a passive investor cannot demand to co-invest in such deals.

- Passive investors occasionally augment or liquidate holdings, providing opportunities for active investors to capture liquidity premiums.

The following chart, taken from the paper, summarizes average annual turnovers for passive investors seeking to track large U.S. stocks (the S&P 500 Index), small U.S. stocks (the Russell 2000 Index), investment-grade corporate bonds and high-yield corporate bonds (Bank of America Merrill Lynch, BAML, bond indexes). Results indicate that even passive investors may have large portfolio turnover that varies by asset class.

In summary, active investors have opportunities to capture premiums from passive investors because: (1) passive investors must trade to track the market (benchmark indexes); and (2) real passive investors sometimes augment or liquidate holdings.

Cautions regarding conclusions include:

- As noted in the paper, the value added by active managers may typically be less than their fees. Finding a manager with expected net outperformance is difficult.

- Also as noted in the paper, even though active managers can outperform, passive investment choices help keep active management fees in check.