“Overview of Financial Market Regime Change” states that researchers often use return volatility to discriminate financial market regimes (intervals of persistent behavior). Investors often use some variation of simple moving average (SMA) crossovers to determine market regime. Do these perspectives intersect? To investigate, we examine realized volatility (standard deviation of daily returns) and frequency of days with extreme returns during bull and bear regimes as defined by the S&P 500 Index being above or below its 200-day SMA. We define extreme days based on standard deviations from the mean daily return over the prior 1000 trading days (about four years). These definitions avoid look-ahead bias. Using daily S&P 500 Index closes (excluding dividends) for January 1950 through July 2011 (with the first four years used only to set initial thresholds for extreme days), we find that:

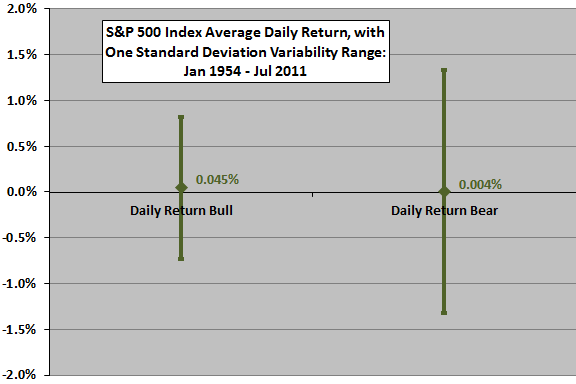

The following chart summarizes the average daily returns of the S&P 500 Index, with one standard deviation variability ranges, for bull and bear stock market regimes during January 1954 through most of July 2011. Over this period, the market is in a bull (bear) regime 68.3% (31.7%) of the time. Results show that the average daily return is much lower, and the volatility of daily returns much higher, during the bear market regime.

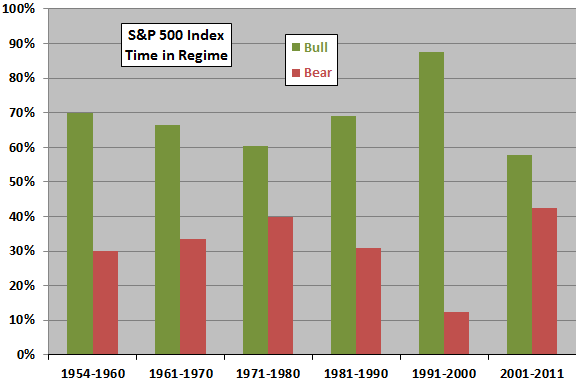

As a robustness check, we look at decade subperiods.

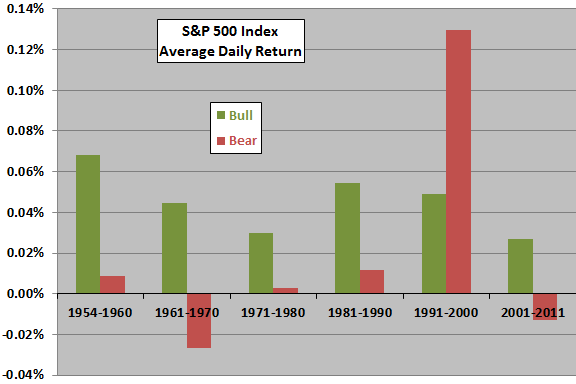

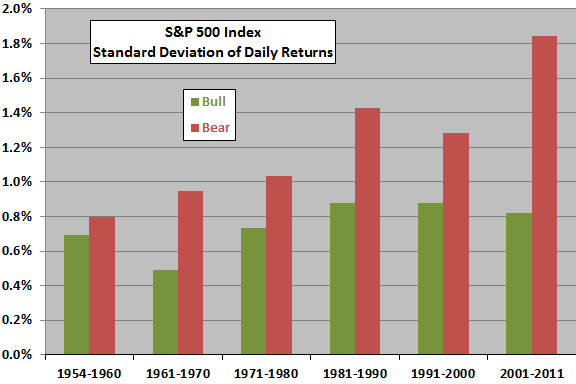

The next three charts summarize S&P 500 Index time in regime, average daily return and standard deviation of daily returns by decade over the sample period. Results show that:

- The bear regime is unusually rare during 1991-2000.

- The average daily return is lower during the bear market regime in all decades except 1991-2000, during which it is notably higher.

- The volatility (standard deviation) of daily returns is consistently higher during the bear market regime and trends upward over the subperiods.

Volatility more consistently agrees with the SMA discriminator than average return.

What about the frequency of days with extreme returns during bull and bear regimes?

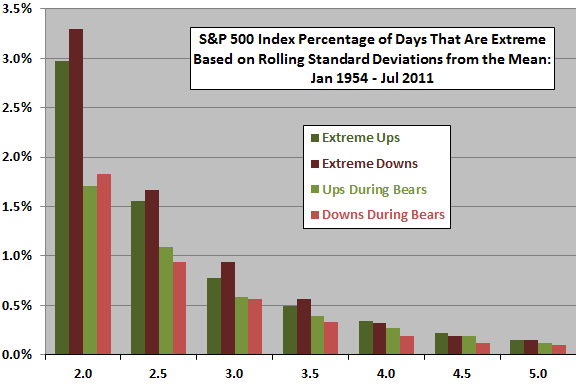

The next chart summarizes the frequencies of extreme days, as defined by standard deviations from the mean over a rolling four-year historical window, during bull and bear market regimes over the sample period. The horizontal axis indicates degrees of extremity ranging from two to five standard deviations from the mean.

Results show that both up and down extreme days concentrate disproportionately in the bear regime. In general (but not perfectly), the more extreme the daily return, the more likely the day is to fall in a bear regime. For example:

- 58% (55%) of extreme up (down) days with returns more than two standard deviations from the mean fall in the bear regime.

- 81% (71%) of extreme up (down) days with returns more than five standard deviations from the mean fall in the bear regime.

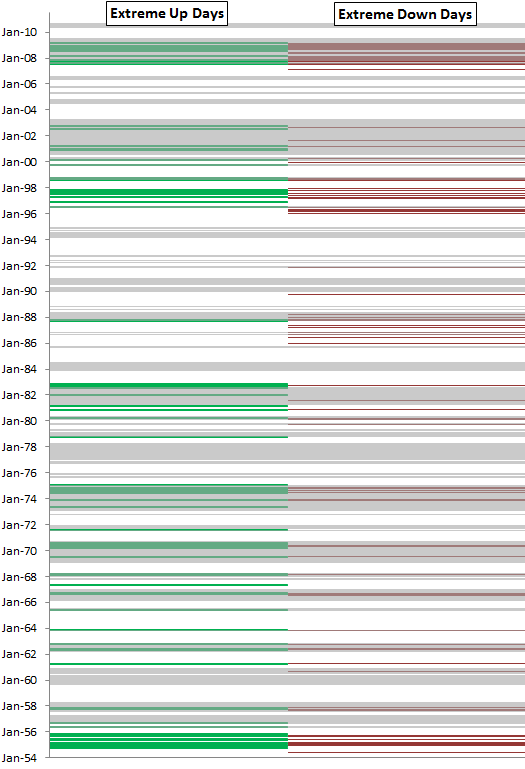

A more granular depiction shows extreme day clustering.

The final chart depicts the timing of all days with returns more than three standard deviations from the mean (per the rolling four-year historical window) over the sample period. It shows that both extreme up days and extreme down days tend to cluster in the bear market regime (shaded intervals).

In summary, evidence from simple tests indicates that a commonly used bull-bear stock market discriminator more consistently identifies a high-volatility state than a low-return state.

Cautions regarding findings include:

- As noted, extreme day definitions are relative to a rolling four-year history, not absolute return levels. While a four-year history neutralizes the political cycle, it may not be the most insightful choice.

- Results may not apply to other asset classes.